H.P. Lovecraft was a horribly racist, bigoted shut in who was letdown by a lot of people in his youth. Stricken by night terrors, agoraphobia, and heavy depression, the world of the early 1900s was in no way prepared to address his mental health. He was doomed to become the sort of person we actively work to disassociate with Americanism here in the twenty-woketeen.

Of course, that’s not really what we do here. In the U.S., we have no choice but to accept that almost all of our fruits of greatness fall from a poisoned tree. The spacecraft that took us to the moon was designed by a Nazi rocket scientist we secretly pardoned, and eventually re-branded as a nice, quirky foreign genius. Our founding fathers designed a radical new government to enable people to live a life free from tyranny, knowing they stole the land from the people that owned it prior, and stole the people they needed to build it.

In a narrower lens, Lovecraft’s breakthrough blending of existential dread and cosmic curiosity created a genre of science fiction so poignant that we’ve made absolutely no attempt to dissociate it from him. “Lovecraftian” is so tightly bound to the concepts of forbidden knowledge, eldritch ancientism, and the collapse of society, that we sort of surrender to how carelessly simple of a descriptor it’s become.

That later point seems ever more salient these days. Like superhero movies and zombie fiction, our collective nihilist anxiety has us creating and consuming fiction that feeds these dark fantasies at breakneck speeds. Either we need big budget hamster wheel amusements that check our feel good boxes at a reliable clip, or we need the play in our imaginary necessity for rugged individualism in case our neighbors turn into some unrecognizable other overnight. Considering a lot of Lovecraftian fiction stems from the author’s deep xenophobia, it’s not a stretch to say that things that seem old and gone are never really old or gone for very long.

So when people co-opt “Lovecraftian” without making any attempt to engage or dissect what the man himself was saying about his society at the time, I become a little weary. Repeating problematic tropes just because you don’t know or agree that they’re problematic doesn’t make you less complicit in the harm they could do. The cyclical nature of how blackface becomes a scandal every Halloween season should be example enough of this.

This is, mercifully and understandably, too much baggage to bring to a game like Sea Salt. I don’t know what intentions the Swedish team at Y/CJ/Y had when approaching the source material. Did they mean to design a game that somewhat subverts both this horror subgenre and the standard strategy game? Probably not. But the end result gets close.

Instead of placing players in the position of “truth seeking” everyman just looking to avoid doom (as games in this narrative space often do), Sea Salt makes you the sum of all of these fears. As Dagon, lord of the Deep Ones, you are feared as the almighty deity you are by the local human civilization. They live to placate your hunger, and when their leader refuses to give you what you demand – his life in sacrifice – you decide that a divine purge is the only solution.

I find casting the play as the evil god to be an interesting choice. Often in H.P.’s mythos, it can be hard to understand what makes these Great Old Ones so terrifying besides the fact that they just are. They exist on the fringes, and those in contact with him become babbling husks, hapless prey, or monstrous beasts. Also, much of these stories most problematic elements stem from the fear of change happening to the establishment by the hands of “the others.” Sea Salt isn’t making some sort of political statement by flipping the script here – this isn’t a scaly skinned Django Unchained. But to be represented truly as The Transformer, in all your terrible agency, makes the lore feel different. Maybe people who play as The Killers in Dead by Daylight have a new appreciation for their favorite horror slashers in a similar way?

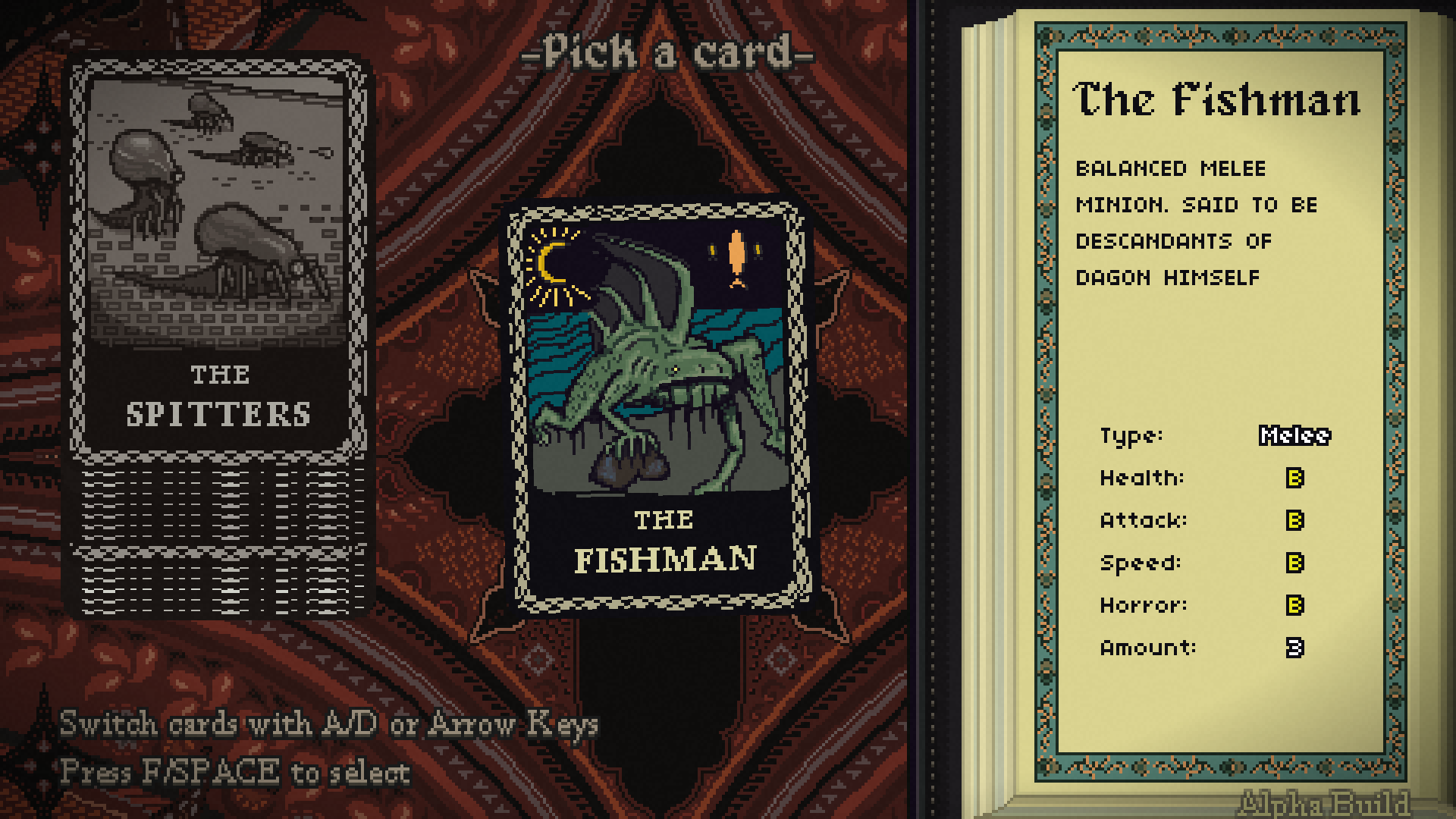

As a literal god, you can’t be bothered to actually go to the land and reap the flesh of the heretics personally. You delegate that to your apostles, demi-gods with unique strengths.They don’t get their hands dirty directly either – that’s the job for the minions. You directly control this horde of bugs, fishmen, and cultists, as they warble through towns, forests, and sewers to reduce the local population to zero.

Apostles empower these death clouds. They determine what sorts of creepy crawlers make up your initial horde. They can also grant passive buffs to particular types of monsters, or create certain restrictions for your kill team in exchange for power. For example, one of your underlords restricts your swarm to just a lich, who can make specters out of slain foes. In trade, these killer ghosts won’t fade away over time as they normally do.

Controlling this horrible cloud feels a bit like a most fast-and-loose Pikmin. Your cursor tells the beasts where you want them to go, and it’s up to them to find their own best route to that position. With a press and hold of a button, you commence the killing, and all monsters will find the nearest thing they can touch and shred it.

This can become hectic, because different monsters move at different speeds and have different attack ranges. You may want all of your horde focused on a particular group of shotgun-wielding jamokes, but should a random bystander pass within range of some of your troop, they will peel to give chase. This almost always puts them in the perfect position to get killed. There is a kind of art to be developed in ensuring your monsters hit your intended target reliably, but you never feel like you’ve mastered the process, even after a few hours of play.

There are a surprising amount of units that can be recruited for this purge, most of which you unlock throughout the adventure. It becomes incredibly difficult to determine the role of each of these creatures, though. Or more plainly, I don’t know why I would pick some units like worms or swarms, when crabs and fishmen seem just as capable of doing everything they do, but better. When the goal is to just kill everyone, and you don’t necessarily need any alternate ways to do that, besides run forward and beat face, your don’t become very incentivized to pick anything besides a large amount of a couple “sure things.”

I do sort of love the game’s audacity to even try this sort of mechanic, though. It feels like a more hands-on Clash of Clans. The mix of your auto attacking squad is a temperamental science, but without the element of timing, it becomes more of a gamble than a strategy game. And even though Sea Salt sends lots of Pikmin vibes, there’s no puzzles or pacing switches to really add much diversity to the experience.

This “reverse-horror” game plays with genre expectations in a lot of ways. In shifting the perspective from prey to predator, Sea Salt defines itself in a growing cloud of content that wears Lovecraft like a designer suit, with no interest in whose fingers got pricked during the sewing process. The gameplay, though thematically rich and theoretically provocative, had me wishing I could play this game in a way that offered either more control of my outcomes or a greater amount of divergent content.

This game was reviewed on a PC with a review code provided by a PR representative of the game.