About Best Ofs

This article is one of the “Best of Irrational Passions”, meaning it’s featured on our Best Of page. Along with it, we have both a full read-through of the article and a conversation about the article, the writing process, and where the author is with the piece. Give it a listen! And if that’s how you found this page, we hope you enjoyed!

This is the first entry in what will be a monthly recurring column titled, “The Art of the Video Game.” In this column, I hope to examine the inherent interdisciplinary nature of video games as an art form and their relationships with other art forms. The column will begin with broad discussions about medium before delving in more closely to examine specific video games and artworks.

Video games, like many other art forms, have the ability to transport the player into another place and time, into fictional worlds, and unimaginable situations. As one of the newest forms of art, video games have undoubtedly borrowed, or at least been influenced by older art forms. I like to think of mediums of art as a sort of venn diagram and in this article we’ll be looking at the specific overlap between painting and video games.

In 1960, writer and art critic, Clement Greenberg wrote an essay titled “Modernist Painting.” In it, Greenberg put forth the notion of medium specificity, an idea that individual artistic mediums held certain specific characteristics that made them uniquely different from all other artistic mediums. He claimed that for art to become independent, for it to be acknowledged as its own specific medium, it must embrace those aspects which it does not share with any other art form, or those aspects which are specific only to it. To further elucidate his notion of medium specificity, Greenberg discusses painting and identifies its specific characteristic as flatness. Flatness, he argues, more so than any other aspect is an unique characteristic that belongs solely to painting.

While flatness may define painting, it is far more interesting to examine the ways in which painting has worked in order to counteract that one defining quality. While it is true that certain modernist painters—most notably Piet Mondrian—have embraced flatness, historically, painting has sought to disown this definition at every turn. It is here, in the rejection of the flat that painting and video games most closely resemble one another.

Video games, which present fully 3D worlds have the inherent task of representing a three dimensional space on a two dimensional screen. Even VR, for all its innovations and promises does not change the fact that display screens are essentially modern day canvases. While this could be said of any art form which is displayed on a screen, painting and video games are unique in that they often ask for or require suspension of disbelief. They ask the viewer, if only for a moment, to forget that they are playing a game or staring at a painting and believe that they are inhabiting or gazing upon a world which is real. If you are wondering how this is different from film or television the differences are subtle but there. Film and television are experienced in a relatively passive manner; you sit and watch. Video games require constant and active engagement. Painting, while seemingly passive as well, is a much more intimate experience. It is generally believed that you don’t look at a painting the same way you look at a movie. When you’re in a museum looking at a framed canvas on the wall that is all you are doing. You are absorbed both physically and mentally in it.

Art is often lauded or panned on its ability to make the beholder believe in its authenticity. Game reviews for The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, Bioshock, and Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End all feature praise for the degree to which they give the player “authenticity,” “believability,” and “immersion.” While game critics are busy praising video games for their ability to depict realistic worlds, art critics have been doing the same with paintings for centuries. Michael Fried’s book, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and the Beholder in the Age of Diderot, discusses the observations of Denis Diderot, the father of modern art criticism, while at the French Salon of 1767. When commenting on Jean-Baptiste Le Prince’s Pastorale Russe, Diderot remarks, “I actually find myself there.” He goes on to describe the ways in which certain paintings draw him in and allow him to mentally inhabit the realm of the painting. What is a seemingly flat, two dimensional canvas sudden becomes a portal into another world. Video games, by their very nature pull players into their worlds. Gamers are forced to virtually inhabit the world of the game, to interact with it and participate in the actions of the fictional environment.

A decidedly older medium than video games, painting has long had to convince viewers to suspend their disbelief in the illusion presented to them. There is a certain technique in painting which is called “trompe-l’oeil” or “trick of the eye” which refers to a style of realistic perspective painting which makes flat surfaces look like realistic three dimensional objects and spaces. This type of illusionistic painting has its roots in Ancient Greece. In his book, Trompe-l’oeil: The Eye Deceived, Martin Battersby tells the tale of of 5th century Greek painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius. The story goes that the latter challenged the former to a competition to see who could paint the most realistic painting. Zeuxis painted grapes so realistic that birds attempted to peck at them but was still forced to concede victory to Parrhasius when he demanded that Parrhasius remove the curtain over his painting only to discover that his painting was the curtain.

Trompe-l’oeil has gained prominence—most notably during the Italian Baroque. In these cases, the technique is often used to make a space seem larger than it actually is or to compensate for architectural shortcomings. For example, the church of Sant’Ignazio in Rome does not have a dome but a perspectival painting of the interior of the dome so that when visitors stand in a particular spot along the center of the church and look up they perceive the building to be domed.

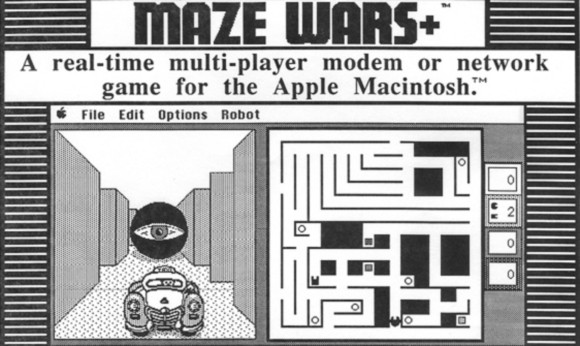

Game designers share the same challenges as baroque artists, how do you represent three dimensions on a two dimensional screen? Now, having digital screens capable of showing moving images makes this challenge much easier for game designers but the techniques in achieving a three dimensional representation are the same. It all comes down to perspective. This is something that even the first first-person game, Maze War (1974) understood. To be able to properly and accurately depict a three dimensional environment, perspective and depth of field must work in a similar nature to how it does in real life. Games like Sim City (1993) or Starcraft 2 (2010) present three dimensional worlds but do so not through one or two point perspective but through axonometric and isometric views—views that are impossible to see in real life.

For as long as painting has existed it has sought to replicate real life. The story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius serves as a parable towards the representational power of painting to depict lifelike three dimensional images. In recent years, as graphical fidelity has begun to increase, video games have sought to capture that sense of representational awe that Parrhasius’ painting did. Certain moments throughout gaming’s history have already proved that video games are fully capable of depicting realistic three dimensional environments. Remember the first time you stepped out of the sewers in The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006) and were greeted to a seemingly endless expanse of lush green countryside to explore? How about the first time you saw Half-Life 2 and were let loose on the incredibly detailed and realistic City 17? Or, how about only a few months ago when Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016) released and gamers were treated to, what I think, is the most beautiful video game ever made?

Just as Denis Diderot found himself within the world of 18th century French painting, gamers everywhere find themselves inside the worlds in which games present. As gamers, when we play games with meticulously constructed worlds it feels as if we have been there. Despite what has always been a medium which has been experienced two dimensionally, video games have been able to reject that inherent limitation—just like painting—and provide deeply rich and fleshed out three dimensional worlds.