In the last entry into “The Art of the Video Game” series I discussed the nature of painting and its similarities to video games. If you haven’t read it I recommend checking it out here. In that piece I brought up the immersive qualities of painting and referenced Michael Fried’s Absorption and Theatricality. What I didn’t mention was what Fried believed was necessary for a painting to be truly immersive, the subject(s) of the painting need to be wholly absorbed in whatever they are doing to the point that they ignore the beholder. If the subject acknowledged the beholder (and likewise the painter) then they become aware that they are in a painting and that they are on view. If the subject is absorbed in their actions on the canvas and remained oblivious to the viewer then they appear to be in a scene in which the beholder can be immersed. Keep this logic in mind, it will be important later.

Moving away from painting, I would like to focus the attention of this piece to a new artistic medium, theatre.

Theatre, unlike most mediums, relies on the ability of live performers. There is a quality inherent to live theatre that separates it from a similar medium such as film and that is variation. A live performance of any kind is bound to have variations, no matter how small. Witnessing one performance is not the same as witnessing another. Similarly, no two playthroughs of a video game are the same. That is to say, there is a distinctly human element in both mediums that not only accounts for, but requires variation. Experiencing theatre and experiencing a video game are entirely unique experiences in a literal sense.

Experientially and emotionally, interacting with any form of art is always a unique experience because of the nature and variation of human thought, emotion, and perception. Two people can stand side by side staring at the Mona Lisa and have drastically different experiences.

Seeing “The Lion King” on Broadway in New York is different from seeing it performed in San Francisco a week later. Perhaps a line was delivered slightly differently or an understudy had to fill in for an ailing actor. Likewise, playing even the most linear game varies from playthrough to playthrough.

Art is meant to be engrossing, immersive, and thought-provoking. Typically these qualities are achieved as Fried argues but ignoring the beholder. If you become aware that what you are viewing and/or watching knows that it is being watched you start to lose your sense of immersion. The thing is, art is aware of this, theatre in particular. When you examine the medium of theatre from an objective standpoint, nothing about it should feel immersive. You are sitting in a room surrounded by hundreds of other people, staring at a stage, and watching a fictional production. Nothing about it is real, yet the performance relies on the actor’s ability to make you think it is, if even for just a moment, just enough time to feel something.

The truth of the matter is that you are your own biggest deceiver. You intentionally suspend your disbelief in the fiction taking place on stage and buy into it yourself. Video games, arguably, are even more fake. You are often playing them in your home, while holding a controller, staring at a TV screen, and looking at less than photorealistic images. Nothing about it is real whatsoever but we allow ourselves to buy into the fiction of the game just as we allow ourselves to become wrapped up in a production on stage.

On the surface level, video games seem to have one distinct quality that separates them from most other art forms: interactivity. We often refer to traditional arts like painting, sculpture, film, and theatre as passive art forms. Examples of art that require no interaction or participation by the viewer to exist or to experience. Yet, this is not entirely true. Participatory art is alive and well outside of video games and in fact, theatre itself has a strong affiliation with interactivity. As Claire Bishop, professor in the Art History department at CUNY Graduate Center, notes in her book Participation, “the explosion of new technologies and the breakdown of medium-specific art in the 1960s provided myriad opportunities for physically engaging the viewer in a work of art.”

Bishop goes on to discuss a more relevant form of participatory art, Brechtian theatre. She notes the ways in which Brechtian theatre presents situations which intentionally interrupt the narrative through a disruptive element that causes audiences to break their identification with the protagonists on stage and be incited to critical distance. Brechtian theatre compels the audience to take up a position towards the action and relies on raising the consciousness of the spectator through the distance of critical thinking. This form of engagement is quite the opposite of traditional theatre and conventional notions of immersion. While a typical audience can sit and easily become immersed in the representation of narrative on stage, the Brechtian audience is purposely forces out of that comfort and daze and asked to engage critically with the work, a form of participation in itself.

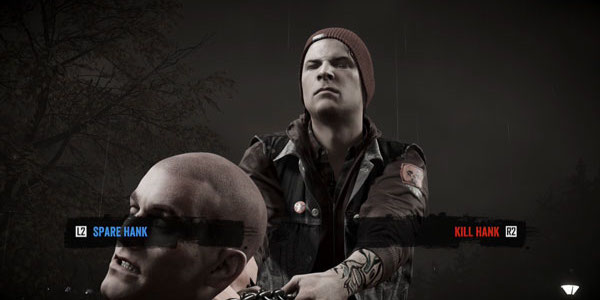

Think of Brechtian theatre as a sort of fourth wall breaking moment of audience engagement. Nearly every video game offers up moments that demand that the player make a divergent choice. Think the Good/Evil options in the inFamous series or any of the hundreds of choices that need to be made in a Telltale game. In these situations, video games are borrowing directly from Brechtian theatre by submitting to the will and decisions of the player. These often story-critical moments are meant to be difficult, meant to incite critical thinking on the part of the player and get them to truly consider their own role in the game as opposed to being a passive observer of the story.

Guy Debord, co-founder of the Situationist International, advocated that the construction of “situations” was the logical development for Brechtian theatre with one crucial difference: they would involve the audience function disappearing altogether in the new category of viveur (one who lives). Rather than simply awakening the critical consciousness as in the Brechtian model, “constructed situations” aimed to produce new social relationships and thus new social realities. The transition from audience/beholder to viveur or producer/participant is one in which the audience is just as responsible for the art as the creator.

If Brechtian theatre is an example of how video games ask players for situational input during story critical moments then what Debord proposes is more akin to the very nature of video games themselves. While they are not the only form of participatory art, video games certainly rely on participation more than any other medium. By that logic then, the player has always been a viveur, there is no game without the player and indeed the experience of the game and the artistic qualities inherent in them are defined as much by the player as they are by the game developers.